Zen aesthetics

cannot be separated from its ethics, whose goal is satori through

self-awareness, and these seven principles are tools for such awareness through

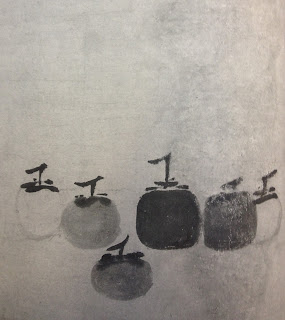

aesthetical action. The action has to be asymmetrical, for in asymmetry there

is incompleteness and therefore movement and change, giving a living reference

for an experience that is basically looking for a general sense of

imperturbability inside motion. Asymmetry is complexity and is to be balanced

by a principle of simplicity both in actions and means. Both principles can be synthesized

without much effort in the quick movements of calligraphy, or in the calm

representations of the artificially combed landscape of a stone garden, as long

as we maintain the third principle as the aesthetical attractor or engine for

our art: austere sublimity. “Sublime” should be understood as being bony and

not sensuous, as Hisamatsu proposes, or in other words, sublime is the

non-human dimension of the experience, the overwhelming universality of

individual life sailing its streams of time. Japanese haikai represent this

sense of universality in their first verse. “Austere” modifies “sublime”

redirecting its possible stormy connotations into the realm of sparse objects

and relations, certainly what characterizes better Zen aesthetics in relation

to other artistic proposals. On the other hand, the principle of naturalness

focuses the artistic action outside the social milieu and the use of art for other purposes than the mystical experience. Here there is an obvious

contradiction, for the Zen artist tries deliberately to be natural and not

artificial, furthermore, assumes the seven principles, which are far from being

natural guidelines to action. The contradiction is somewhat minimized through

the principle of profound subtlety and the call for an egoless art, after all,

Zen Buddhism is the Japanese development of the Mahayana Chang Buddhism, a

non-dual metaphysical proposal, but ego is precisely a very natural phenomenon

of animal life, and any reduction of the ego is a reduction of vitality. In

this sense, Zen crushes violently with the Nietzschean aesthetics of vitalism

which pervaded the avant-garde and still drives today the art markets responsible

for our ideas of what art should be. The principle of freedom from attachment

widens the gap with our present vitalism-capitalism even more, making of Zen

art a marginal discourse fit only for the selected temples of the critics and

other chosen priests. Finally, the principle of tranquility becomes too often

in our society a mere death wish, or the desire of a massage after a long day

at the office, and not a seasoned ataraxia (imperturbability) that assigns its pondered

value to the fleeting phantoms of our social life. If we do not stress our

minds our encephalograms become flat and our heart shrinks into empty

desperation.

An

alternative to Zen aesthetics was developed by the New York abstract

expressionism in music and painting. Though some of the roots of such

aesthetics is Zen itself (as is the case of John Cage) or a general interest in

Japanese culture (not exempt of remorse) after WW2, there is another root for stillness,

like the one we observe in Feldman and Rothko, that is more related to desert

landscapes of the mind provided by life in modern cities, places where anxiety

and compulsion look for a cure in any stillness dance. It found its room in the

corporate hallways of Manhattan, where the religion of genius still gives an

alibi for art merchandizing, translating the austere sublimity of simple

still-life composing into the sublime emptiness of money. Back in 1984,

precisely while I was studying with Feldman, I was trying to find my way

between a meditative need for meaning in the peak of the cold war, a

mathematical drive for clarity, and the wild hormones of a young vitalism which

had me running from one thing to another. I found myself in the hands of the

crippled symmetry of modern art, building ultra-civilized sound landscapes which

opened my mind to blue distances of nostalgia but shut the door for the

development of any aesthetics of life. Nonetheless, after more than 30 years

thinking about the subject and practicing it in my music and painting, I still

think that there is an element of Zen

aesthetics (and any aesthetics of the universal law in general) that makes

sense for any vitalist art: the uncompromised drive for clarity and simplicity

that life needs in its symbolical complexification processes.

Comments

Post a Comment

Please write here your comments